The Power of Tone of Voice in Life Science Marketing – Part 2

By David Chapin

SUMMARY

VOLUME 11

, NUMER 3

Tone of voice is a powerful tool for differentiating your life science offerings. Unfortunately, it is often ignored. In the second in a series on tone of voice in marketing, I introduce a new way of developing a tone of voice, one that can be easily shared across your entire life science marketing team—and beyond.

Tone of voice is important, yet too many life science marketing organizations ignore this powerful tool.

In this series on the role of tone of voice in life science marketing, I’m making several key points:

- Tone of voice is clearly perceived by your audiences.

- Tone of voice is one way to influence the impressions your audiences have of you. Specifically, it can help differentiate your organization and offerings.

- Most life science marketing organizations underutilize tone of voice as a tool in marketing and sales.

- There are effective systems you can use to first define tone of voice, and then encourage consistency in its use.

- Do you have a document that defines the appropriate tone of voice for your organization? Is this document widely shared? Is it understood as the “bible” for your communications? (Many organizations have a related document—one that prescribes a set of logo usage standards. Unfortunately, this document usually doesn’t define the appropriate tone of voice. And even this document mostly sits on a dusty shelf somewhere; it is used only rarely to correct or guide graphic communications. Most employees outside the marketing and communications departments—and even perhaps some inside—are not aware of the importance of consistency in communications, or that any guidelines even exist.)

- If you do have such a document, how clearly does it define the appropriate—and inappropriate—tone of voice? Does it specify exactly what your tone should be? Does it give lots of examples, both good and bad? (Most documents only offer mild exhortations, such as this real-life example: “Our corporate values should be expressed in communication and design – in other words, they serve as reference points for all communications.” Well, if your corporate values include terms like Innovation or Passion, how exactly is an employee supposed to translate that into the appropriate tone?)

- Does the document give you recommended vocabulary, not as a mandated list of words that “must be used,” but as a set of guideposts to encourage employees to adopt the correct tone? (Almost none of the documents I’ve ever reviewed include recommendations or specifics. As I’ll discuss in the next issue, the proper use of “guiding vocabulary” is one of the most powerful ways to create consistency in tone of voice across all voices in the organization.)

- choose an appropriate tone

- implement it every place it’s appropriate

- stick to it; that is, keep your tone consistent

- Harmonized—in sync with your positioning and UVP

- Authentic—true to your organization and your values

- Clear—transparent and easy to understand

- Unique—distinct from your major competitors

- Sustainable—able to be maintained consistently

- Meaningful—resonates with your audience

- Formal vs. Casual

- Enthusiastic vs. Matter of Fact

- Serious vs. Funny

- Respectful vs. Irreverent

- the Clown

- the Scientist

- the Ruler

- the Child

- the Rebel

- the Artist

- Find a differentiated tone of voice

- Fine tune the subtleties of your tone

- Create a forward-looking tool that can guide the creation of additional content with the correct tone

- Share this tool with others; that is, to democratize the creation of a consistent tone of voice.

With this as a thesis, let’s begin by asking how effectively your organization is at harnessing the power of tone of voice.

How well does your life science marketing organization harness tone of voice?

Here are some questions to help you determine how well your organization is harnessing the power of tone of voice.

Tone of voice is an underutilized resource for differentiation.

How’d you do with these questions—does your organization harness tone of voice? If your organization is like most, you’re not harnessing or ensuring the consistency of your tone of voice at all, or certainly not to the extent you could.

Which brings me back to the first point in my thesis: tone of voice matters. It’s an effective and powerful tool that enables you to control the impression your audience has of you. In the last issue I examined some research from The Nielsen/Nelson Group (the N/N Group) that showed that tone of voice is both noticeable by your audiences and influences their perceptions. If this finding is valid, the implication is clear: tone of voice can be used to differentiate your organization and offerings.

Does tone of voice really influence audience perception?

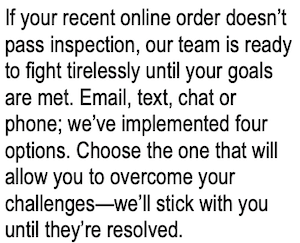

Can tone of voice influence audience perception? To test this important question, I conducted some research, asking respondents (US adults, aged 18 and up) to score their impressions of two organizations, based on paragraphs from hypothetical websites (see figure 1). I was looking to see if tone of voice could clearly convey different attributes or traits that an organization might use to differentiate themselves: “persistence” or “taking care of you.”

Figure 1. Does tone of voice influence audience perceptions of an organization? Respondents were shown these paragraphs (in random order) and asked to judge on a 7-point Likert scale their impressions of each organization’s focus on “persistence” or “taking care of you.”

These paragraphs were written as if they would be used on an e-commerce website. The basic structure of the paragraphs is the same: statement of problem, options for getting in touch, and call to action. The only real difference between the two is tone of voice, as conveyed (primarily) by vocabulary.

The paragraph on the left was written to try to convey more “persistence.” The one on the right was written to convey more of an attitude of “taking care of you.” Would survey respondents perceive this difference?

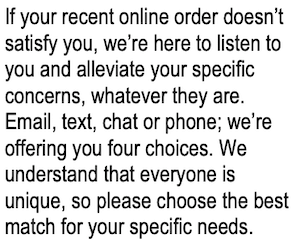

The results from 25 survey respondents are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Respondents rated each paragraph independently on a 7-point Likert scale for “Persistence” and for “Taking care of you.” The most frequent answers are plotted here. Differences between the two paragraphs are clearly perceived. Respondents attribute more “Persistence” to one organization, and more “Taking care of you” to another. In other words, differences in tone of voice are perceived by respondents.

The results are clear: the two attributes are clearly perceived by respondents—based on just a few dozen words that conveyed exactly the same information.

Tone of voice communicates; tone of voice differentiates.

Differentiation is crucial in life science marketing.

Of course, your efforts at differentiation should start with your positioning and your unique value proposition (UVP). Once you’ve nailed those, adding tone of voice, done correctly, can be a powerful amplifier.

Choosing the right tone of voice.

If you decide to harness tone of voice, how can you do so effectively? It’s a simple process, at least in theory:

Unfortunately, the first and last steps—choosing an appropriate tone and then keeping it consistent—are both surprisingly difficult.

What is the “appropriate” tone for your organization? There are six main criteria:

Defining your tone of voice in life science marketing.

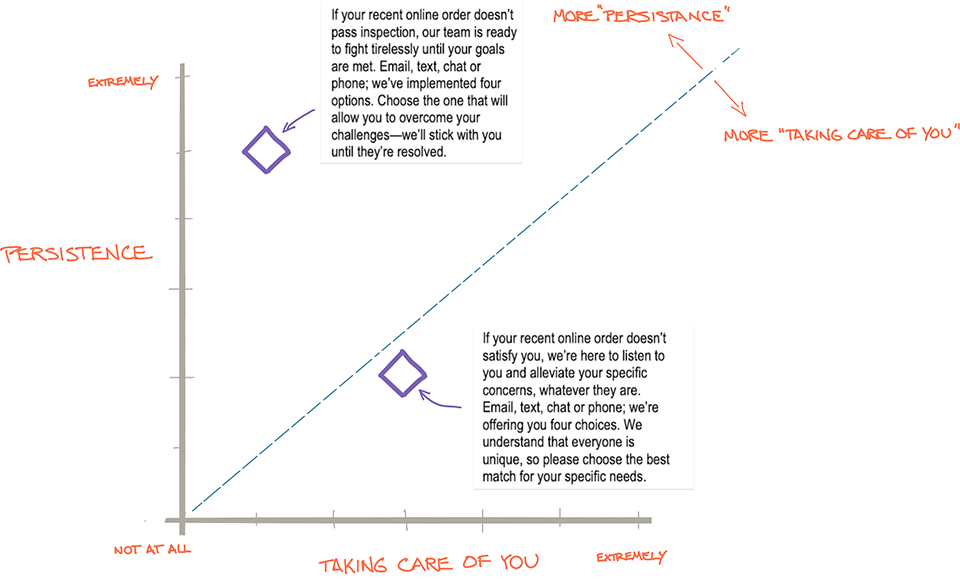

Once you’ve defined your positioning and UVP, how do you define your tone of voice? In the last issue I outlined one system, based on 4 spectra that the Nielsen/Nelson Group (the N/N Group) developed. These spectra are:

Figure 3. The four spectra defined by the Nielson/Norman Group offer one way to define your tone of voice.

While using these spectra might work in theory, it is difficult in practice. There are many interrelated challenges, with two major ones: First, the system doesn’t make it easy to find a differentiated, unique tone. Second, it’s difficult to use these to guide the creation of new content with the correct tone.

Finding a differentiated tone of voice.

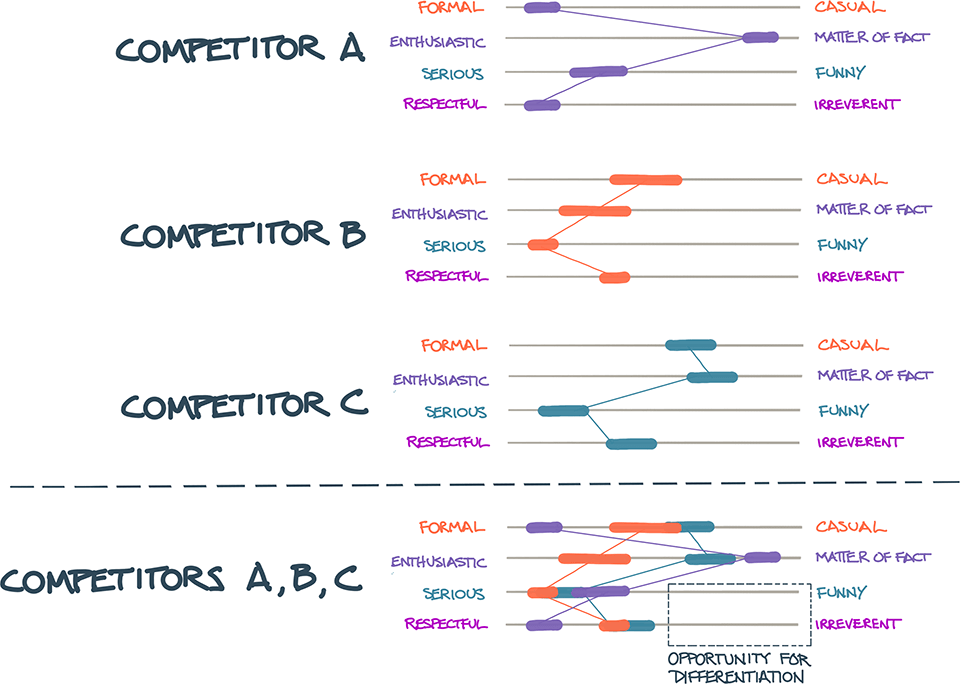

To see the implications of this, let’s imagine you’ve decided to conduct a tone-of-voice audit on your competitors. To do so properly, you’d visit the web sites of your major competitors, and score each one using these four spectra. Then you’d identify a tone to differentiate you from your competitors.

Now imagine that your audit is complete, and the results are shown in Figure 4. Each competitor is shown separately, and then all the scores are overlapped at the bottom. Is there room for a unique tone of voice?

Figure 4. If you audited three of your competitors and determined that their tones of voice are those shown here, how would you use this information to select a differentiated tone of voice that meets all the relevant criteria: Harmonized, Authentic, Clear, Unique, Sustainable, Meaningful?

The bottom diagram in Figure 4 reveals that there are two attributes that are underutilized: Funny (as opposed to Serious) and Irreverent (as opposed to Respectful). That tone of voice might be attractive—simply because it’s so different.

And this brings us to the second major issue with using these spectra on an ongoing basis. They do not provide forward-looking guidance; that is, it’s difficult to use these spectra to create a consistent tone of voice.

In this example, the opportunity for differentiation lies in creating a tone of voice that is Funny and Irreverent. Is this really the tone of voice you’d want? Maybe there’s a set of really good reasons that no one else has claimed this space.

And even if you answer in the affirmative, pulling this off is going to be quite difficult; harnessing humor requires walking a fine line. Cross it, and you’ll be seen as silly or stupid. And if you are able to do it once, does the use of these spectra make it easier to do this consistently, year after year?

This is just one example, but it highlights the difficulty of creating and maintaining a differentiated tone of voice.

Are these spectra forward-looking, or backward-looking?

People with these skills do exist; Forma employs several. But relying on each and every employee to have the skills matching those of your best copywriters is a recipe for an inconsistent tone of voice. Remember that all employees are “ambassadors” for your organization; we need a system that can democratize the creation of copy with the proper tone, because the copywriting skills of your entire employee set is going to vary widely.

And this highlights another problem with these spectra. They are a coarse yardstick that is mostly useful after the fact. It is difficult to use them as a proactive guide; it would be hard for every employee to use them to create copy with the appropriate tone.

Are these spectra useful in consistently creating copy with the correct tone?

For example, how would you use these spectra to drive consistency in use? If your manager gave you the “target” shown in Figure 5 as the ideal tone of voice, and asked you to create some copy for a LinkedIn post, where would you begin, and how would you know whether you had succeeded? Yes, a trained copywriter could do it, but what about every employee in your marketing department, or in your entire organization? That’s a lot less likely.

Figure 5. How would you create copy that meets the target as defined by these spectra? These are useful after the fact, but they are a poor roadmap for the forward-looking creation of content.

Furthermore, could you use these spectra to guide multiple people in the creation of appropriate content? That is can you imagine using these spectra to ensure that every employee posting on LinkedIn uses just the right tone?

There’s a better way to select and define tone of voice.

Each archetype is associated with a specific tone of voice.

Each archetype has a particular tone of voice. Here is a list of a few common archetypes; as you read it, ask yourself what the tone of voice would be for each, and if they would be different from each other?

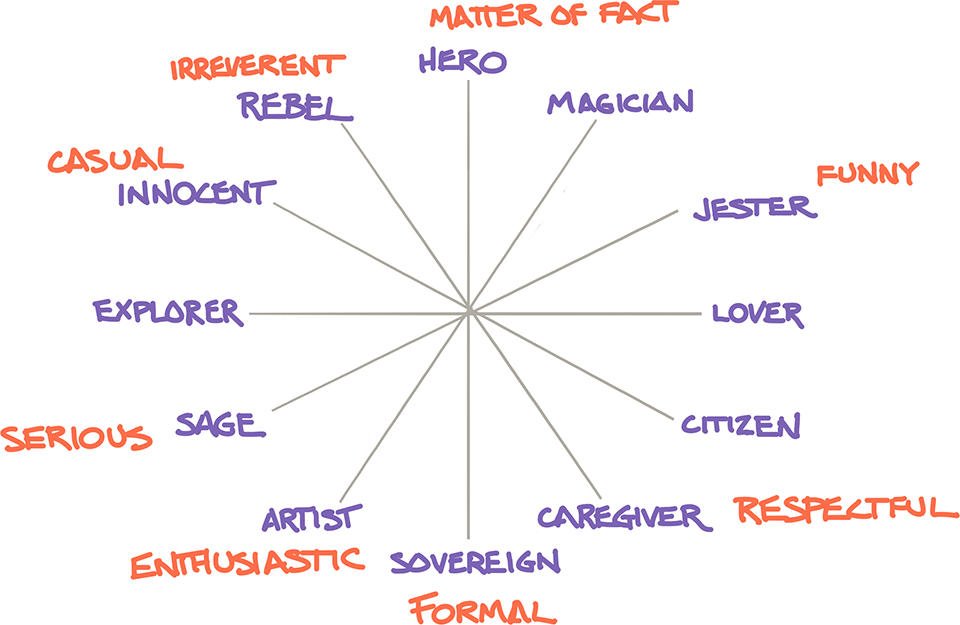

The mention of each of these labels brings to mind its own unique tone of voice, doesn’t it? Rulers, using the N/N Group labels, will tend to be Serious; Rebels will tend to be Irreverent; Jesters will tend to be Funny. These tendencies are shown in figure 6, as are the other labels from the N/N Group spectra.

Figure 6: Each archetype is associated with a set of behaviors, including a specific tone of voice. The labels from the N/N Group are shown here in red, associated with specific archetypes.

Archetypes seem to offer many more options for tonal expression than are outlined in the N/N Group’s spectra. And this provides many more opportunities to proactively pick an archetype (and a set of attributes) for positive reasons, rather than the essentially reactive decision I outlined above, using the spectra from the N/N group.

The use of Archetypes makes it easier to define a tone of voice that is unique from your competitors.

Since one of the primary uses of archetypes is differentiation, an archetype should always be chosen with a clear understanding of your competitors’ archetypes (or lack thereof). And since there are literally several thousands of archetypes, it is easier to find a unique one for your organization.

The use of Archetypes makes it easier to find a tone of voice that is subtly and distinctly yours.

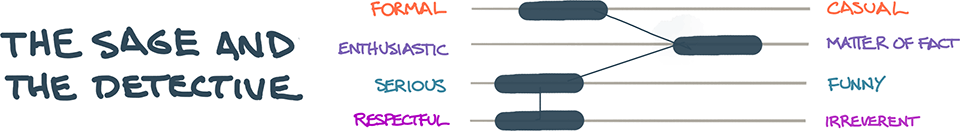

Each archetype has its own tone of voice. And these are distinct, even though the scores on the spectra from the N/N Group might be similar—or even the same. For example, consider two archetypes: the Sage and the Detective. Both would score similarly on the N/N spectra, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Both the Sage and the Detective would score similarly on the N/N Group’s spectra, but would have discernibly different tones of voice. The Sage would be more confident, while the Detective would be more curious.

But the Sage and the Detective have very distinct behavioral patterns. The Sage is self-assured; the Detective may be more questioning. One simple way this might show up: the Sage could use more declarative sentences while the Detective could use more questions.

In this way, archetypes are a more subtle tool than the N/N Group’s spectra for guiding the choice and implementation of a clear, distinct tone of voice.

The use of Archetypes makes it easier to find a finely-gradated tone of voice.

There are thousands of archetypes, and this makes it easy to identify a very specific one—to harmonize with your positioning, UVP and the appropriate tone of voice. Unlike many other organizations that use archetypes, at Forma we create customized archetypes for each organization, with underlying attributes unique to each team and corporate culture. This makes it easier to identify, fine-tune, and harness the correct tone of voice.

The use of Archetypes makes it easier to create a forward-looking tool, one that can guide content creation.

And, as it turns out, it is easy to augment these instructions to increase the consistency of the results. I’ll cover some of the ways to accomplish this in the next issue.

The use of Archetypes makes it easier to share—that is, for others to create the appropriate tone of voice.

Archetypes are a powerful tool in life science marketing.

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, archetypes, when used properly, deliver many other benefits in addition to guiding tone of voice. They are a tried and true system for augmenting differentiation among life science organizations. They can improve internal branding (also known as “employer branding”) while driving alignment among teams of employees. We also have data that shows they can improve team performance and employee engagement.

Archetypes represent the common patterns that are embedded in our culture. They represent a set of shared behaviors and attributes. Among these is a common tone of voice. To put this another way, Jesters tend to talk alike, to have a similar tone of voice. So do all other archetypes, Scientists, Caregivers, Sages, Heroes, Innovators, etc., etc.

Maybe that’s why their contribution to tone of voice seems to be overlooked. I’m not aware of anyone else who is discussing this issue (and if you are, I’d appreciate you letting me know so I can contribute to the dialog).

In sum, the use of archetypes makes it easy to:

There are many pitfalls in implementing archetypes in life science marketing.

Be warned: Archetypes are a powerful marketing tool, with applications well beyond tone of voice. As such, they must be handled carefully and used correctly.

I have seen the use of archetypes backfire, both strategically and tactically. Strategically, your archetype (and tone of voice) must be chosen to harmonize with your Unique Value Proposition and your Positioning. In addition, your archetype (and tone of voice) must be clearly defined. Remember, while each “main” archetype has a generally consistent tone of voice, there are many flavors within each archetype, each with its own tone of voice. For example, there are many types of detectives, such as hyper-rational (Sherlock Holmes), brute force (Dirty Harry), suave and sophisticated (Hercule Poirot), and nerdy, technical genius (Abby Sciuto, from the TV show NCIS). Each would have their own tone of voice; only one of them would ever say something like, “Go ahead, make my day, punk.” (At least, non-ironically.)

Your archetype can also fail through poor tactical implementation. Follow-through is critical. If you introduce your archetype in the wrong way, or if you introduce it and don’t reinforce it correctly, your employees will see it as just another “management fad.”

How can you use archetypes to clarify your tone of voice, and drive consistency in its use? I’ll cover this topic in my next issue. For now, I’ll leave you with one hint: words are powerful things.

The Marketing of Science is published by Forma Life Science Marketing approximately ten times per year. To subscribe to this free publication, email us at info@formalifesciencemarketing.com.

David Chapin is author of the book “The Marketing of Science: Making the Complex Compelling,” available now from Rockbench Press and on Amazon. He was named Best Consultant in the inaugural 2013 BDO Triangle Life Science Awards. David serves on the board of NCBio.

David has a Bachelor’s degree in Physics from Swarthmore College and a Master’s degree in Design from NC State University. He is the named inventor on more than forty patents in the US and abroad. His work has been recognized by AIGA, and featured in publications such as the Harvard Business Review, ID magazine, Print magazine, Design News magazine and Medical Marketing and Media. David has authored articles published by Life Science Leader, Impact, and PharmaExec magazines and MedAd News. He has taught at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill and at the College of Design at NC State University. He has lectured and presented to numerous groups about various topics in marketing.

Forma Life Science Marketing is a leading marketing firm for life science, companies. Forma works with life science organizations to increase marketing effectiveness and drive revenue, differentiate organizations, focus their messages and align their employee teams. Forma distills and communicates complex messages into compelling communications; we make the complex compelling.

© 2024 Forma Life Science Marketing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted without obtaining written permission from Forma Life Science Marketing.