Using Marketing And Sales To Double Your Profit In The Life Sciences.

By David Chapin

SUMMARY

VOLUME 8

, NUMER 3

If your boss directed you to double your profit, what specific steps would you take? In this issue, I look at some interesting case studies that indicate how you could achieve this desirable goal.

Marketing can double your profit in the life sciences. This is not an outrageous claim.

As strange as it may seem, there are cases where life science companies actually don’t want to drive more sales. In general, these companies have a different, but related, goal: more profit and higher margins. Because these cases are so valuable and instructive, I will explore them as we discuss ways to double your profit.

I’ll begin this issue by examining the common misconception that “marketing = promotion,” and I’ll do so by asking a simple question. What value does marketing provide to your life science business? Ask most life science executives that question and they will answer that their marketing efforts…

- Build awareness, which leads to…

- An increased number of leads, at which point sales takes over and delivers…

- An increased number of opportunities to close business, which leads to…

- An increased number of closed deals, which leads to…

- An increase in revenue, which leads to…

- Company growth.

In this view (which I’m obviously simplifying), life science marketing equals promotion. Promoting a life science business correctly leads to awareness, which leads to sales opportunities, which leads to more revenue.

It’s interesting to note that the story above is not about profit or profit margin. In most peoples’ minds, life science marketing leads to revenue. Whether that revenue leads in turn to profit is not typically part of marketing’s responsibilities. But of course this view, notwithstanding its simplified presentation, is limited. If you examine the definitions of marketing used in business schools, they include much more than just promotion. One of the standard definitions of marketing is known as the 7 Ps; it springs from the classic theory of the Marketing Mix, as revised by Booms and Bitner in 1981. The 7 Ps are:

- Product

- Price

- Place

- Promotion

- Physical evidence

- People

- Process

This definition of marketing includes much more than just Promotion. By including Price, this expanded view makes it clear that marketing’s purview also extends to Profit and Margins.

What life science organization needs higher margins?

Well, that’s a silly question, isn’t it? Every life science business could use higher margins. But as I learned when studying science, the way you frame the question has a lot to do with the utility of the answer. So if we frame the question as “Who needs higher margins?” then the answer is trivial. But if we frame the question another way —”Are there life science organizations that need marketing to deliver primarily more profit and higher margins, rather than leads, sales opportunities and revenue?” — then the answer can be much more useful.

There are at least two categories of life science organizations that are interested primarily in using marketing to increase profit and margins, rather than just delivering more leads, sales opportunities and revenue. Of course there may be more than two, but I’ll focus on these two in this issue. With tongue firmly in cheek and a tip of the hat to Booms and Bitner, I’m calling them the two Cs.

- Commodities: those life science organizations that supply something that the market views as a commodity — for our purposes, life science products or services with little differentiation in the minds of the customer. Examples might include products or services that are entry level or “low-end.” I’m sure your life science organization has experienced competitive pressures to reduce price and therefore to reduce features. Many suppliers in a given life science sector typically have an offering like this, with a focus on a “low-end” set of features and a correspondingly low cost.

- Capacity: those life science organizations with limited ability to increase the supply of their products or services. Two examples come to mind and both have some resource constraints. First are those life science service companies that are constrained by limited personnel. If the people needed to implement the offered services require significant training, the supply of these people is limited and competition for these people is severe, then ramping up the offering can be very difficult. Second are those life science products that are made in plants running at capacity. For manufacturing processes that are regulated, such as fine chemicals or API, bringing a new plant on line and obtaining the requisite approvals can take years, so capacity is essentially frozen at current levels.

In these cases of limited Capacity or severe Commoditization, more leads really won’t do much good. Higher profit and margins, on the other hand, could be just the thing. To see why, it just takes a little math.

Let’s do the math about life science profit.

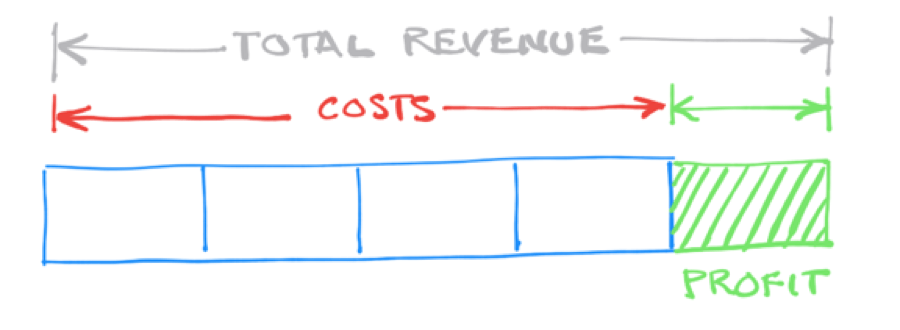

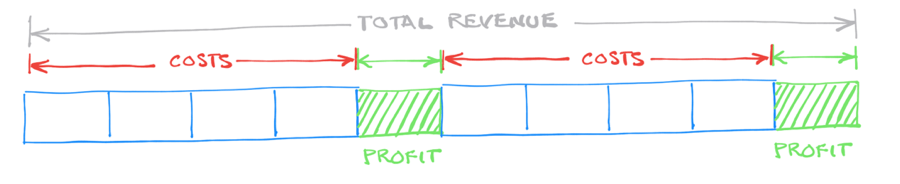

If your CEO walked into your office and demanded that you double your life science company’s profit “or else,” how exactly would you do that? Let’s assume, as in Figure 1, that profit is currently a hefty 20% (one fifth) of total revenue.

Figure 1: Profit is one fifth of total revenue, or 20%. Costs make up the remaining 80%.

To double your profit, there are three main “levers” you can pull: sales, costs and prices. Let’s examine the effect of pulling each one.

Increase sales. To double your profit by pulling on the “sales” lever, you have to double your sales, as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2: One way to double the dollar amount of your profit is to double your total sales (assuming that your profit margin will stay constant as sales increase).

Figure 2: One way to double the dollar amount of your profit is to double your total sales (assuming that your profit margin will stay constant as sales increase).

But doubling your sales is very difficult. After all, if it was easy, you would have done it already. For those life science companies whose offering is seen as a commodity, market forces prevent a rapid doubling of sales. And for those life science companies that are capacity constrained, doubling sales is impossible, at least in the short term.

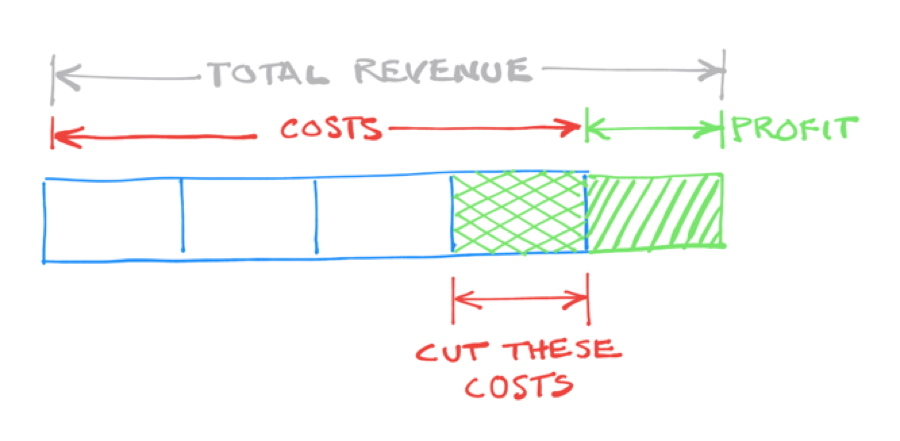

Cut costs. To double your profit by pulling on the “costs” lever, you’d have to cut your costs as shown in figure 3. This is difficult. If your profit margin is 1/n, you must cut costs by 1/(n-1); a number which is larger.

Figure 3: The second way to double your profit is to cut costs, while leaving sales and price intact.

Life science companies with small profit margins (say, 2.5%, or 1/40), must cut just about the same amount out of their costs (2.564% or 1/39). But life science companies with larger profit margins must cut a proportionately larger share out of their costs. In our example where profit is 20% (1/5), life science companies must cut 25% (1/4) out of their costs to double their profit. Cutting this much out of your costs is difficult, if not impossible. And it’s worth noting that cutting costs essentially requires that your life science organization pay for the increase in margins by forgoing the purchase of goods and services that offer a real benefit to your organization.

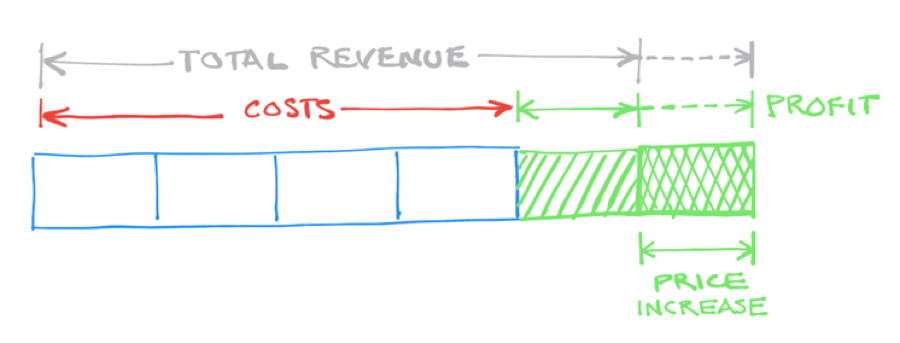

Increase prices. To double your profit by pulling on the “price” lever, you must increase your price by the same percentage as your margin, as shown in figure 4. For example, if your total revenue is $100 and your costs are $80, then your profit is $20 (20%). To double your profit to $40 (40%), you need to leave costs the same while raising your price by an amount equal to your profit ($20). Now your total revenue is $120, of which $40 is profit and $80 is cost.

Figure 4: The third way to double your profit is to increase your price, while leaving costs untouched.

If you make a 5% profit, you only need to increase your prices 5% to double your profit. That’s an amazing statement. A small price increase can double your profit. In contrast to cost cutting, in this scenario your customers pay for the increase in profit. In some cases, raising prices might be difficult. But, as we’ll see, not in all cases.

All things considered, which lever is the most attractive way to double your profit? The answer is simple and unequivocal: Raising prices! Compared to doubling sales, you’ll do less work. Compared to cutting costs, your customers will pay for the increases in profit. And it’s not as difficult as it might first appear.

“But we can’t increase prices!”

At this point, I can hear the protests: “But we can’t increase prices; our life science customers won’t stand for it. If it was easy to raise prices, we would already have done so, and we would be inviting even more much competition.”

I’d like to challenge you on that belief. Simply put, it’s not true.

If you do any reading on pricing theory, as I have, you realize how truly arbitrary prices are. It turns out that prospects and customers are extremely susceptible to having their view of the value of your offering altered—either subtly or in major ways.

In fact, price is the common expression of the perceived value your life science customers have of your offering. I’ll talk more about pricing in future white papers; for now, I’ll look specifically at applied pricing theory and, more important, how to lay the groundwork for effectively altering your customers’ perception of the value of your life science services or products. To start, let’s review a bit of microeconomic theory.

Supply and demand for life science organizations with commodity products or services.

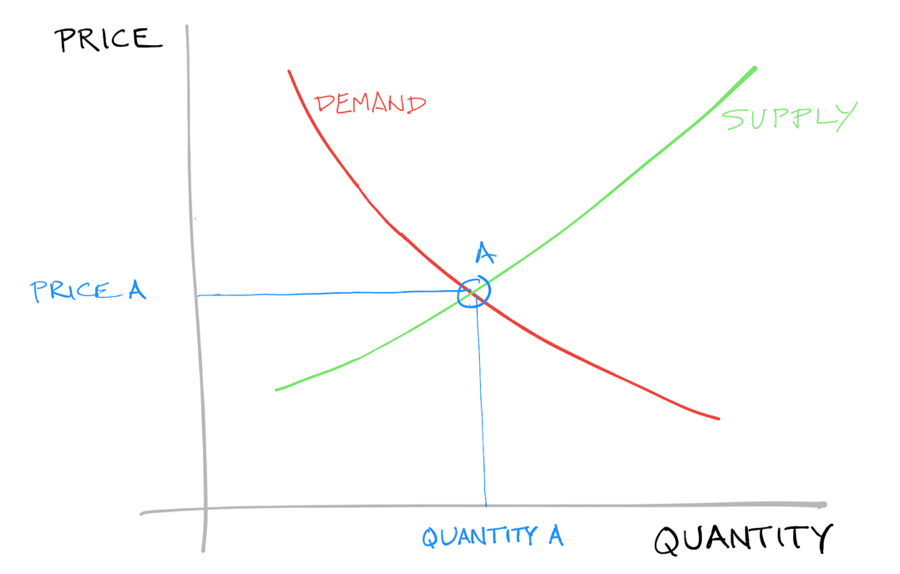

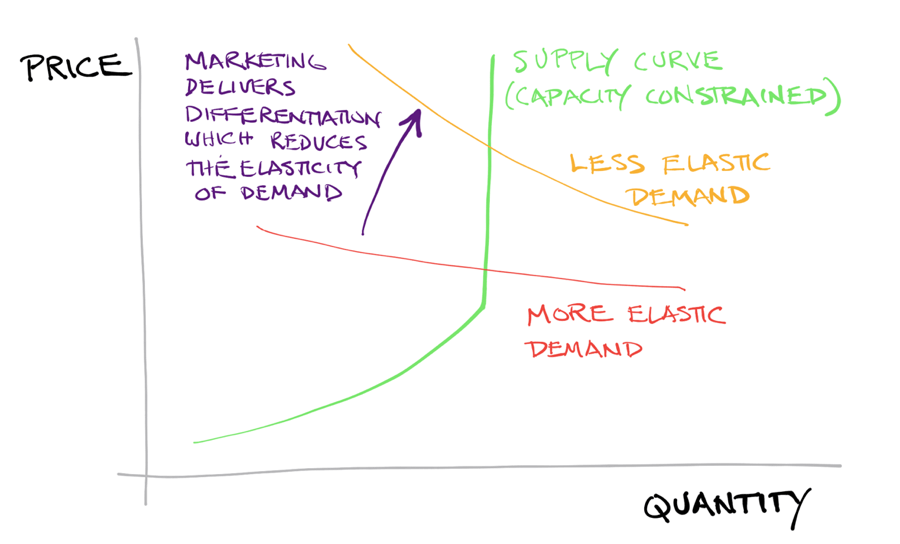

The theory of supply and demand is quite simple; its two key components are captured in the classic graph which relates price to quantity. The “demand” curve, shown in red in Figure 5, graphs the theory of demand: as the price increases the demand generally drops. The “supply” curve, shown in green, graphs the theory of supply: as the price increases, firms will increase the supply by producing a greater quantity. (For those of you who are having a flashback to your sophomore economics class, point A is the “equilibrium point” at which the supply curve intersects the demand curve. I won’t be focused on equilibrium points in this article.)

Figure 5: This graph shows the intersecting curves of supply and demand from classic microeconomic theory.

Given this background, let’s look again at our two Cs: Capacity constraints and Commodities.

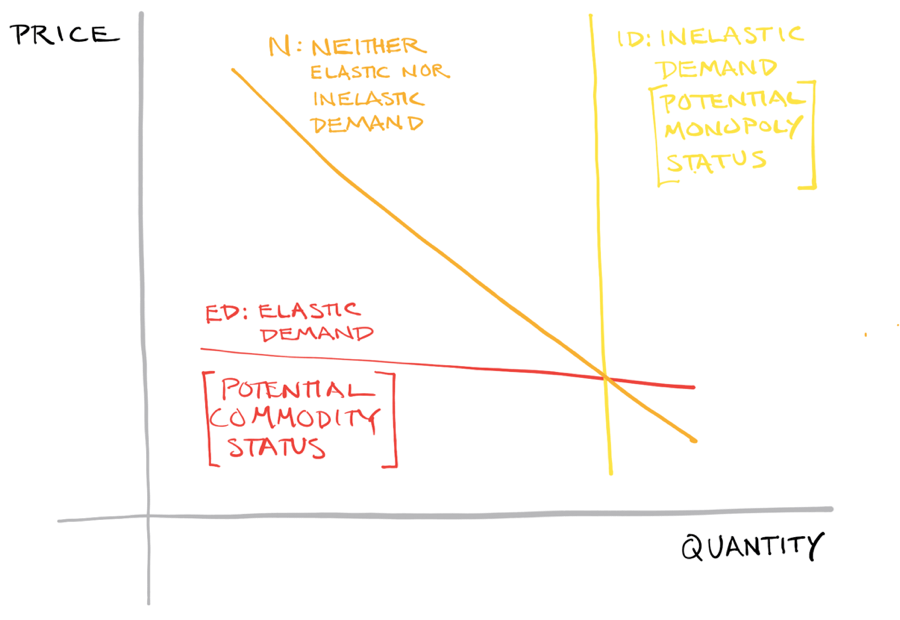

Those life science firms facing commodity status cannot raise prices without suffering a large loss in sales volume. Since buyers see all products in the marketplace as essentially equivalent, any increase in price from any one life science supplier will cause a shift in demand to other suppliers. This “elastic demand” curve for life science commodities is shown in figure 6. Because of the almost horizontal slope of this demand curve — caused by the fact that buyers see all products in the market as equivalent substitutes — the slightest increase in price will cause a large drop in quantity sold.

Figure 6: Different types of demands. Elastic and inelastic demand curves are shown here, along with a demand curve that is neither completely elastic nor inelastic.

The opposite situation, “inelastic demand,” is shown in yellow. One way to think about inelastic demand is to imagine a monopoly: because the product is unique and there are no other equivalent substitutes, any price may be charged for a given quantity, or to put this another way, price increases do not significantly affect demand.

Supply and demand for life science organizations with capacity constraints.

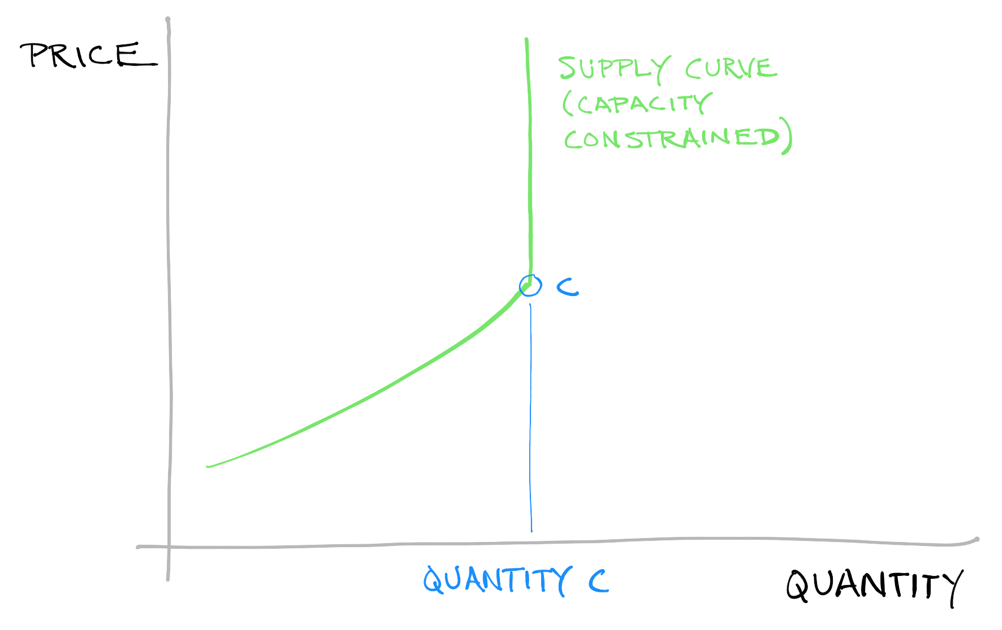

Now let’s turn our attention to a life science supplier with capacity constraints, graphed by the supply curve in Figure 7. Below the point marked Quantity C, production is elastic, that is, the organization can produce more or less, depending upon demand. But above that point, production is inelastic. No matter how high the price may rise, the supplier cannot produce any more, at least not in the short term. This is the case when capacity is limited by resource constraints.

Figure 7: A supplier with capacity constraints can respond to changes in market demand only up to a point, labeled C. Beyond that point, no more quantity can be produced, no matter how high the price offered.

In both the two “C” situations (Capacity constraints and Commodity) the life science organizations seem to be stuck, subject to the whims of constraints they can’t control.

Raising life science prices may not be as difficult as it seems.

So how can I claim that raising prices in these situations is not as difficult as it seems? Let me explain. Remember that the price of a product or service is only a representation of its perceived value. And this representation is somewhat arbitrary, because it’s the perception of value that counts, not the absolute value. If we change the perception of a life science product or service, we can change the value, which means we have more control over price than we might imagine.

It’s easy to find examples of the arbitrariness of value and price. Consider a short-sleeved knit shirt with a collar. A typical shirt without an embroidered logo costs significantly less than the exact same shirt with a logo from Polo or Izod. A box of spaghetti adorned with a “house brand” in the grocery store costs significantly less the exact same spaghetti from the same factory packaged under a well-known brand name. In these cases there is no difference between the products or services themselves, yet the prices—based on the perceived values—are different. The only difference is one of perception. And customers are willing to pay for perception, often quite significantly.

The inability to raise prices during Capacity-constrained or Commodity situations.

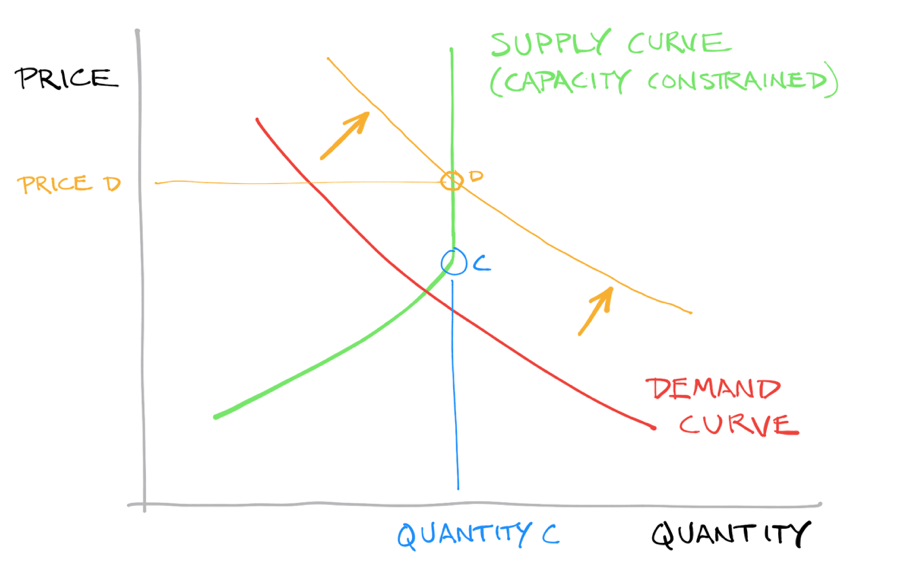

The inability to raise prices for both Capacity-constrained and Commodities comes from the presence of competition offering interchangeable products and services which spreads the demand across multiple life science suppliers. If the products and services were not interchangeable (which would be the case if the organization had no competition), demand would be concentrated on a single supplier’s offering. In the Capacity-constrained situation, what would be the result? As shown in Figure 8, prices would be higher, despite the lack of ability to produce more.

Figure 8. Without competition, demand could drive prices higher for companies that are limited in the capacity they can produce. In this figure, lack of competition shifts the demand curve, which results in higher prices (labeled Price D), even when capacity is constrained.

Now let’s consider our Commodity example. Customers won’t pay a premium for products or services because demand is spread among life science suppliers whose offerings are perceived as identical. This is a crucial point. Without a perceived difference between offerings, there is no perceived difference in value.

In other words, difference is the precursor to any perception of value. But difference alone is not sufficient; the difference must be valued by the prospect—that’s when true differentiation exists.

To clarify the distinction between mere difference and true differentiation, consider a red-haired insurance salesperson. This person may be different, but they’re not differentiated, because having red hair doesn’t add value for customers. In contrast, an insurance salesperson who offers the guaranteed lowest price or who responds to any request within 30 minutes is truly differentiated, because low price and rapid response are both valued by customers.

Competitors’ offerings limit your ability to raise prices only to the extent that their offerings are seen as identical substitutes for yours. The implication is clear: Differentiation acts to limit the effect of competition, allowing you to raise prices, even in situations where you were previously seen as a Commodity or where your Capacity is limited.

If differentiation acts to limit the effect of competition and thereby increase your profit, you must ask yourself this simple question: Has my life science organization done everything possible to ensure that our offerings are perceived as differently as possible from those of our competitors?

In my experience, many (most?) life science organizations have to answer this question in the negative. If your answer is also “No,” then your ability to raise prices and increase profit has been limited not solely by the actions of your competitors or the regulatory agencies, but in part by your own actions.

How do you differentiate between offerings? The answer is simple: through effective life science marketing, and to a lesser extent, sales.

The absence of true differentiation is where most life science marketing fails.

The gap between mere difference and true differentiation is where so many life science organizations fail in their marketing efforts. They fail to create a perception of uniqueness in ways their customers value. To their prospects, other offerings in the marketplace look identical to their offerings. And if the life science marketing function has failed to create the perception of differentiation, the life science sales function has very little hope of landing business at higher prices and higher margins.

There are many reasons for this failure to differentiate. A few are valid but most—quite frankly—are inexcusable.

Regulatory pressure is one force that impedes the creation of the kind of differentiation which is valued by life science customers. Regulations from the EMA, the FDA and others tend to limit variability in both work process and/or work product in many sectors of the life sciences. Regulatory agencies want to stick with the tried and true, because the tried and true is easier to understand, review, manage and approve. These regulatory pressures act to limit the actual differences between life science products and services. They are a legitimate reason why it might be difficult to create real differentiation.

However: Just because it might be hard doesn’t mean it’s impossible, or that you shouldn’t even try. Many life science organizations don’t seriously attempt to create differentiation—which means that they’re asking their sales teams to sell to demand that is elastic, setting them up for failure or for being forced to close sales at extremely low margins.

Besides lack of trying, many of the other reasons for the failure to create differentiation are simply inexcusable. Your life science offerings should not be interchangeable with your competitors’, even if you are selling the exact same excipient as your competition. In fact, given the importance of differentiation, your life science offerings should never be interchangeable with those of your competitors, especially if you are selling the exact same excipient as your competition.

Reducing the perception of commoditization in the life sciences.

To reduce the perception that your offering is interchangeable with that of your competitors, you must start with proper positioning. Choosing the right position is the most important decision a marketer can make; it is also the most difficult.

I have covered in great detail in previous issues some of the many ways to increase the perceived differentiation between your offering and your competitors’. Here are some resources for your review.

- Competing During an Earthquake (The Need To Specialize). (Vol 1, No 3)

- The Importance of Positioning for Life Science Companies (Vol 1 No 4)

- Crafting A Clear Effective Positioning Statement for Your Life Science Brand (Vol 1, No 6)

- Whatever It Is, It Isn’t Life Science Marketing (Vol 1 No 9)

- Poor Sales Performance? It May Not Be Your Sales Team; It Might Be Your Life Science Marketing Strategy (Vol 4 No 7)

- The Marketing Mechanism of Action and The Importance of Uniqueness (Vol 5 No 7)

- Gaining Differentiation (and Pricing Power) Through The Use of Archetypes In Life Science Marketing (Vol 6 No 2)

In addition to the resources above, pricing theory has a lot to teach us about how we can reduce the effects of commoditization, and gain the power to raise prices (and margins). I’ll be covering more about pricing theory in future issues, but I’ll close this issue by revealing one powerful technique you can use to reduce the perception of commoditization in the life sciences.

An example of putting pricing theory into practice in the life sciences

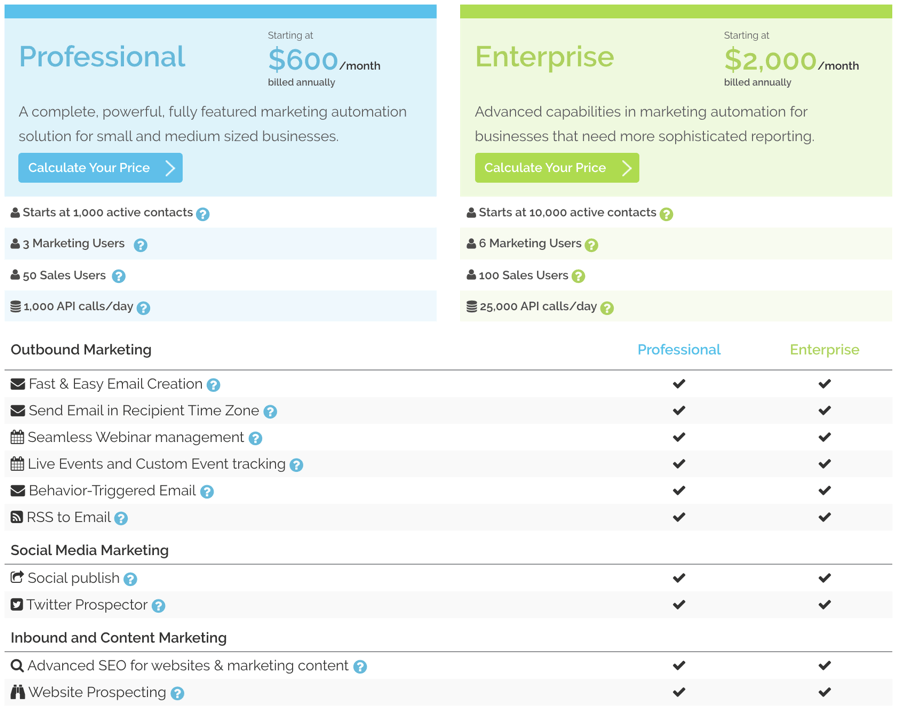

I’ll highlight a real-world pricing technique by examining a purchase many of your organizations have made recently, or are considering: marketing automation software. Many of these services are essentially identical; they allow you to contact, convert, track and score prospects. (For more on marketing automation, see Is your life science organization ready for Marketing Automation? Volume 5, Number 3

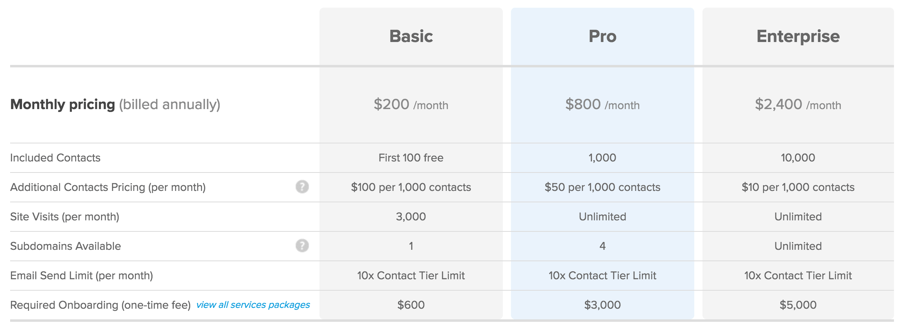

Even though many of these services are essentially identical, the vendors work very hard to differentiate their offering from their competitors’. To see this, examine the two different screen shots shown here.

Figure 9. Note how these two different marketing automation plans offer different features bundled into different packages This makes it difficult to compare the the two plans.

Figure 9. Note how these two different marketing automation plans offer different features bundled into different packages This makes it difficult to compare the the two plans.

The first screen shot is from Hubspot, the second from Act-On. I have not copied the entire list of features, as that list can be very extensive. But I don’t have to copy the entire list to make my point: each vendors bundles different sets of features into different tiers.

If both plans listed the same features, it would be easy to compare the two offerings, and choose the plan with the greatest value, that is: the lowest price. Or if the plans’ components were offered individually, so that you could make independent choices about the different numbers of contacts, the numbers of users etc., it would be easier to compare one service plan against another.

The fact that the options are both limited and bundled together make these plans difficult to compare. They therefore look unique. In other words, bundling together limited options can be a powerful tool to reduce the effect of competition. In addition, bundles allow price segmentation, giving you the ability to split the market into segments that have different perceptions of value and will therefore pay different prices.

How marketing can help life science organizations facing commoditization.

Many life science sectors are facing heavy commoditization pressures because of the behavior of both buyers—who see the sellers and the products and services being sold as interchangeable—and suppliers that are willing to produce these products and services at extremely low margins. These life science firms are facing a demand curve that is horizontal, or almost so. Quite frankly, many of these firms have not taken adequate steps to get themselves out of this situation.

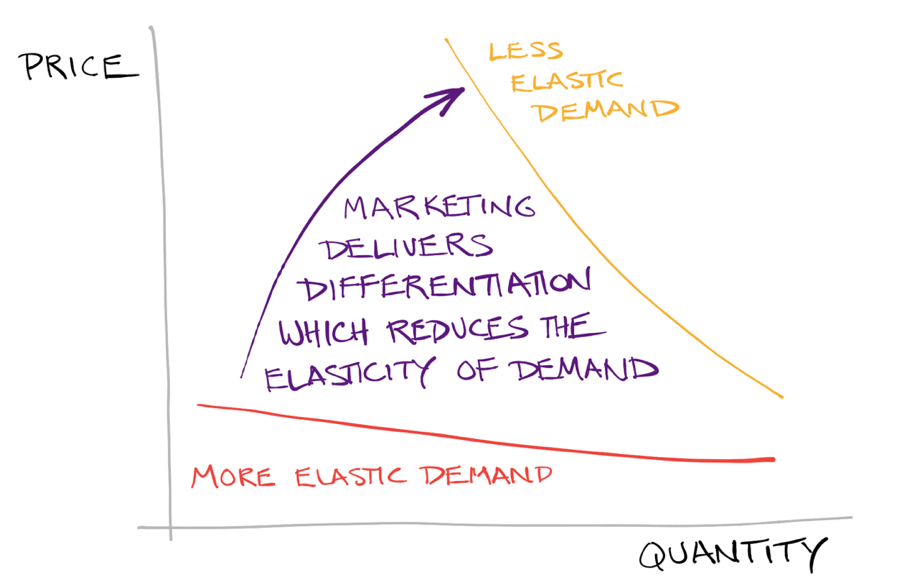

Differentiation can be the difference that shifts the demand curve from elastic (horizontal) towards inelastic (vertical). This differentiation must begin with marketing and be reinforced through sales. The life science marketing function can create this differentiation and the life science sales function can drive it home, protecting life science firms stuck in commodity status from some of the pressures of a competitive marketplace.

Figure 10. Marketing delivers differentiation, reducing the elasticity of demand and allowing you to make more profit.

Figure 10. Marketing delivers differentiation, reducing the elasticity of demand and allowing you to make more profit.

Ironically, many life science firms facing these sorts of commoditization pressures are the ones that put heavy emphasis on sales and almost no emphasis on marketing. Effective life science marketing can help limit the effect of competition, and help make elastic demand more inelastic, allowing differentiation and higher margins.

How marketing can help life science organizations that are capacity constrained or facing commoditization.

Firms facing capacity constraints are limited in the amount they can sell—at least once they reach their production maximum—that is, the point of inelastic supply. Assuming that there is sufficient competition, raising prices under these conditions can be difficult. By reducing the elasticity of demand (through differentiation achieved by positioning and pricing), these life science firms can actually sell their limited products at higher margins, as shown in figure 11.

Figure 11. When capacity is constrained, marketing can deliver differentiation, enabling the organization to charge higher prices and make higher margins.

Summary: to raise life science profit, ensure life science differentiation.

There are three basic ways to increase your profit: increase sales, cut costs, or raise prices. Raising prices is the easiest way to increase your profit but you cannot raise your prices without demonstrating differentiation that is valued by your life science prospects. Many life science companies find this difficult (in many cases unnecessarily so), and therefore they haven’t taken the necessary steps to ensure that their life science offerings are seen as truly differentiated.

There are many tools you can use to create differentiation in the minds of your prospects. You should start with positioning. Once you have a solid position, you can employ many tactics, including the principles of pricing theory, to help you charge higher prices. In this issue, I examined one commonly used pricing technique (bundling a set of limited options) to show how this can help drive higher profit for life science organizations.

Has your life science organization done everything possible to ensure that your offerings are perceived as differently as possible from those of your competitors? If not, why not?

Note

For assistance with interpreting and presenting the microeconomic theory in this article, I am deeply indebted to Wally Thurman, Graduate Faculty and William Neal Reynolds Distinguished Professor at NC State University.

For pointing out the three levers you can pull to adjust profit (sales, costs and price), I am deeply indebted to David Baker of Recourses and Blair Enns of WinWithoutPitching.

The Marketing of Science is published by Forma Life Science Marketing approximately ten times per year. To subscribe to this free publication, email us at info@formalifesciencemarketing.com.

David Chapin is author of the book “The Marketing of Science: Making the Complex Compelling,” available now from Rockbench Press and on Amazon. He was named Best Consultant in the inaugural 2013 BDO Triangle Life Science Awards. David serves on the board of NCBio.

David has a Bachelor’s degree in Physics from Swarthmore College and a Master’s degree in Design from NC State University. He is the named inventor on more than forty patents in the US and abroad. His work has been recognized by AIGA, and featured in publications such as the Harvard Business Review, ID magazine, Print magazine, Design News magazine and Medical Marketing and Media. David has authored articles published by Life Science Leader, Impact, and PharmaExec magazines and MedAd News. He has taught at the Kenan-Flagler Business School at UNC-Chapel Hill and at the College of Design at NC State University. He has lectured and presented to numerous groups about various topics in marketing.

Forma Life Science Marketing is a leading marketing firm for life science, companies. Forma works with life science organizations to increase marketing effectiveness and drive revenue, differentiate organizations, focus their messages and align their employee teams. Forma distills and communicates complex messages into compelling communications; we make the complex compelling.

© 2024 Forma Life Science Marketing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted without obtaining written permission from Forma Life Science Marketing.